Cuban rumba

Birth of the Rumba

Throughout the slave trade, the African slaves who were uprooted and parked in their barracones (barracks) sought to perpetuate their ritual songs. These are accompanied by drums which, when they run out or are taken away, are replaced by anything that is within reach: the edge of a piece of furniture, an empty box…

These same rhythms and songs also help to brighten up the rare free moments of the exhausting days of work. Some of them sketch a few steps of an improvised dance. During these moments of relaxation, the influences of the various African ethnic groups represented mix to produce a purely Cuban secular music. In particular, there is a strong Congo (Yuka and Makuta), Abakuá and, according to Fernando Ortiz, Gangá influence. This process took place locally, on each plantation, although the slaves did not communicate with each other or very rarely.

Following the end of the slave trade and the abolition of slavery at the very end of the 19th century, many freed Africans left the ingenios (sugar mills) and tobacco fields and headed for the small and large cities in search of work. Unfortunately, their hopes did not last long. The former slaves, of all ethnicities, were pushed to the most working-class neighborhoods or to shantytowns, where they rubbed shoulders with the most miserable classes of white society.

Access to employment is very difficult. To occupy these long days, people used to gather during Rumba parties or rumbones in the solares (inner courtyards of the cuarterías, large collective buildings, where poor families were crammed) of Havana, Matanzas and some other cities in the western part of the island. According to the Cuban musicologist Argeliers Léon Pérez, the word “rumba” is part of a family of terms of Afro-American origin that mean “collective meeting/party”. Some believe that the origin of the word is Spanish and derives from “rumbo” which means “on the way” or from “mujer de rumbo” which means a promiscuous girl. Others think that “rumba” derives from the word “kumba” which means “navel” in Kikongo language. During these rumbones, the rhythms of the barracones are reproduced with the help of old cod boxes, wooden pegs (clavijas, origin of the name of the claves) abandoned by the carpenters of navy and left on the quays of the ports, boxes of sails of ships… Each one brings its style, integrates its cultural elements, adds its own variations. The music but also the dances are enriched in this process of transculturation resulting from the rapprochement between the various African ethnic groups. The few white Spaniards who mingle with these musical groups bring some elements of their culture, especially from the Cante Jondo repertoire and Flamenco for the singing. They play a Rumba called Rumba estribillo, a “primal” form articulated around an estribillo (refrain). Because of its origin, it is also called Rumba de solar.

For the rumberos, the music represents a cry of liberation and protest against the social conditions inflicted on them: the struggle against the condition of slavery has been transformed into a fight against marginalization.

Percussionists improve their instruments by choosing the elements that sound best. Sometimes they dismantle wooden boxes, furniture or bad instruments to build their own instruments, wooden boxes called cajón.

The rumbones are becoming more and more frequent. They gather family, neighbors, friends… in every neighborhood. The texts of the Rumba speak about the daily life: love, friendship, betrayal, daily difficulties, death, particular events… or challenge the other musicians or dancers. Little by little, some musicians stand out, either on the cajon or on the voice. Groups are formed around musical directors. The music became structured and at the end of the 19th century, depending on the place, several forms of Rumba could be distinguished, such as the Columbia or the Rumbas, often mimetic, called Rumbas del tiempo España (Rumbas from the time of Spain), such as the Siguirya, the Jiribilla, the Resedá, the Palatino or the Yambú. Thanks to the mobility of workers, these forms of Rumba spread to the capital at the beginning of the 20th century. Guaguancó was then created. Almost all these variants of Rumba have disappeared today and only Guaguancó, Columbia and Yambú remain.

From the end of the 19th century, various Rumba performers, who are known today only by oral tradition because neither the Cuban bourgeoisie nor the American recording companies ventured to the poor neighborhoods of Havana or Matanzas to record them, became legendary. We can mention José ‘Malanga’ Rosario Oviedo (dancer), ‘Papa’ Montero, Estanislá ‘la Rumbera mayor’ Luna (singer and dancers) or ‘Cubela’ (supposed creator of the Columbia in the village of Sabanilla).

During the first part of the 20th century, the coros de clave (vocal ensembles similar to the Spanish orpheons) and later the Coros de Guaguancó (evolution of the coros de clave that specialize in Rumba) took over the Rumba. We can mention Los capirotes, Los rápidos fiñes, La hoja de Guayaba, La tuya or Los roncos in Havana, El paso franco, Carraguao or Los dichosos in its suburbs and later La yaya in Sancti Spíritus and El bando rosado, El bando verde, El liro banco, El flamboyán or Bando azul (formed in 1910) in Matanzas.

In 1906, the musician and composer Ignacio Piñeiro became a member of the coro called Timbre de Oro and later led the coro called Los roncos. During the 1920s, he brought the Rumba out of the solares and integrated it into the repertoire of sextetos soneros.

During the 1920s and 1930s, the coros tended to disappear in favor of ensembles that, without being professional, provided a quality performance. Considered as vulgar with a dance with strong sexual connotation by the high society, the Rumba is proscribed in public places, cafés or cabarets. The groups play from solares to solares. It became frequent that rumberos of a district went to challenge those of another district. These “invaders” often triggered tensions, aggressiveness or fights.

The percussions evolve and the cajones disappear progressively to the profit of the tumbadoras or congas. The claves definitively replaced the small percussion instruments often used until then.

Little by little, the most talented rumberos, trained in contact with the elders in the solares, managed to leave their neighborhoods. Some of them, like Benito ‘Roncona’ González, got the opportunity to play on the airwaves and others, like Agustín Gutiérrez from the coro called Paso Franco, were hired by bands.

From the mid-1930s, the C.M.C.Q radio station broadcast the program La hora sensemaya, hosted by Manuel Cuéllar Vizcaíno and Julito Vázquez, which provided a space for black people to express themselves and offered Rumba a time to be broadcast.

At the end of the 1930’s, Luciano ‘Chano’ Pozo González is noticed as a virtuoso conguero. Quickly, he animates coros and comparsas of which Parampampín or Los Dandys de Belén. Chano’ Pozo is quickly recruited by the big cabarets, in particular in 1940 by the Tropicana for its review Congo pantera. However, the penetration of an exotic-erotic Rumba in the cabarets’ shows, danced by white dancers, naked and without any knowledge of the roots of the genre, did not favor the situation of the Rumba.

Like him, many percussionists, almost all of them from Havana and Matanzas, thanks to their virtuosity, will join the dancing musical formations in the 1940s. However, some of them will take advantage of the Afro-Cuban Jazz in full development in New York to reach the United States and triumph there. Thus, Francisco Raúl Aguabella Pérez, Ramón ‘Mongo’ Santamaría, Candido Camero, Armando Peraza or Carlos ‘Patato’ Valdés left the island in the 1950s.

Cuba, which had an enormous melting pot of musicians, could count on those who remained, the “Aspirina” family, Federico Arístides “Tata Güines” Soto Alejo, “Mañungo”, Manuela Alonso, Enrique Dreke, Alberto Zayas, Trinidad Torregrosa, Jesús “Obanilú” Pérez Pérez or Gonzalo “Tío Tom” Asencio Hernández.

During the 1940s, the Clave and Guaguancó group was structured along the lines of the coros of the beginning of the century. They interpreted the whole repertoire of the Rumba, trying to preserve the original tradition.

In the 1950s, Ricardo ‘Papin’ Abreu created the Papin y sus rumberos formation in Havana. In 1952, Hortensio ‘Virulilla’ Alfonso, Estebán ‘Saldiguera’ Lantrí and Florencio ‘Catalino’ Calle founded the Grupo de Guaguancó marancero, which in 1956 took the name of Los muñequitos de Matanzas after the success of their song entitled “Los muñequitos”. In 1957, the group AfroCuba de Matanzas, more oriented towards the stage, was also born.

The revolution allows the emergence and professionalization of groups from poor neighborhoods. Between 1959 and 1962, the Cuban government showed a great willingness to support Rumba. In 1961, Calixto Callava, employed as a docker, formed the Grupo marítimo portuario zona 5 in the neighborhoods of Havana. Papin y sus rumberos became Los Papines in 1962. The same year, the creation of the Conjunto Folklórico Nacional around authentic rumberos like Gregorio ‘El Goyo’ Hernández, Mario ‘Aspirina’ Jauregui Francis or Juan de Dios ‘El Colo’ Ramos Morejón allowed to preserve the authenticity of a Rumba that was sometimes distorted and threatened by its own success as a show. In 1986, the Grupo marítimo portuario zona 5 reorganized and took the name of Yoruba Andabo to produce a Rumba in the purest tradition.

Today, the Rumba is still practiced in the regions of Havana and Matanzas mainly. The return to the black roots brought to him many young followers. It also irrigates with force the Cuban music, in particular the Timba or what one calls globally the Salsa. It is not rare to find a rhythm or even a passage of Rumba in a current piece (“Los Sitios Entero” of NG la Banda, “Pal bailador” of Isaac Delgado, “Mi Magdalena” of El all stars de la Rumba).

Rumba, Rhumba and others…

The term “rumba” has several very different meanings that should not be confused. The original meaning of this word represents the Cuban music and dance that was just mentioned. Here are some other uses of the word Rumba.

Any work of the teatro vernáculo (theater composed of white actors who wore masks representing black faces) ended with an “end of party” sung by one, two singers or the entire company. When these performances were recorded by the record companies, this final Guaracha was labeled “Final Rumba”, although it was not a final Rumba. It is called Rumba del teatro bufo. The first example goes back to 1899 with “Los rumberos” by Arturo B. Adamini.

At the beginning of the 20th century, some trovadores had difficulty making a living from music. Rejected towards the poor districts as soon as their performance in a cabaret or a coffee shop ends, they mix with the rumbero world. Thus, they sometimes included fragments of Rumba in the heart of their songs. Engraved in 1906 on an Edison cylinder, the title Mamá Teresa gives an example of this Rumba that cannot be confused with the authentic Rumba.

In the 1920s, the Rumba will have a great posterity in the Congo. It will be mixed with the Congolese culture to give the Rumba Congoleña which will know a great success in the years 1940/1950.

From the 1930’s, under the impulse of Xavier Cugat, all rhythmic music coming from Cuba received the name of Rhumba, Ballroom Rumba or Ballroom Rumba in the United States, as the word “Salsa” will later represent everything that sounds “Latino”. The origin of this “h” is still not well understood. This Rhumba, which is nothing else than Son or Conga, has absolutely no connection with Cuban Rumba. It is a commercial exploitation of the music played in Cuba.

Guaracha was adopted by the gypsies of Seville in Spain and Portugal during the 18th century. They gave it the name of Rumba flamenca. It is not directly related to the Rumba practiced by the Cubans. It is the same for the Rumba catalana of the gypsies of Barcelona, invented in the years 1950/1960, which derives from the Rumba flamenca by adding influences of the Son and the Mambo.

The instrumentation

Initially, there was no fixed instrumental format for playing Rumba. The dances and the possession of drums, symbol of grouping and possible rebellion, having been prohibited to the slaves by the Spanish colonists of the 17th to the end of the 18th century, the songs were accompanied by any type of object of the everyday life: edge of a piece of furniture, reversed drawer, crate of cod, case containing the sails of the ships, door, chair, stool, box of cigars, spoon, bottle…

Over time, musicians have managed to recreate drum substitutes called cajones (wooden boxes). They come in 3 sizes (low, medium and high), each one being played with bare hands by a percussionist. It is then frequent that the rhythm called catá, complementary to the clave, is played by a 4th musician with sticks on the edge of the widest cajón, therefore the lowest.

Following the appearance of the coros de Guaguancó, grupos de Guaguancó or agrupaciones de Guaguancó at the beginning of the 20th century, the instrumental format gradually became standardized. This format included percussive instruments such as claves, cajones, guagua or chekerés, but also melodic instruments such as the guitar or the botija or botijuela (an instrument made of clay with a hole through which it is necessary to blow in order to produce a low sound similar to that of a double bass).

From the 1950s, and especially with their title Los muñequitos, recorded in 1952, the group Los muñequitos de Matanzas modified this formation by replacing the 3 cajones with 3 tumbadoras which have the same sound registers and rhythmic functions. The popularity of the group led to a generalization of this more modern format.

In the late 1980s, the Yoruba ensembles Andabo and Clave y Guaguancó introduced batás drums to complement a combination of tumbadoras and cajones.

Nowadays, a Rumba band is almost always composed of :

- a pair of claves that give the rhythm to the whole group of musicians;

- a guagua or cajita china, a piece of bamboo struck with palitos (sticks), which completes the rhythm of the claves. The rhythm that is played is often called catá;

- tumbadoras, now called congas, most often 3 in number, from the lowest to the highest, they are called tumbadora, tumba or salidor (rhythmic base), repicador or segundo (responds to the rhythm of the tumbadora) and quinto (improvises);

- possibly cajones which, nowadays, are only used as a complement to the tumbadoras. They have the same names as the tumbadoras, depending on their size;

- sometimes batás drums that have a melodic function;

- chekerés which mark the strong moments of the music;

- a soloist singer accompanied by a heart.

The rythm

The rhythm changes depending on the type of Rumba played. However, a common point is generally the clave that establishes a rhythmic base that all the other musicians will follow.

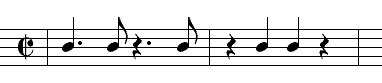

If the Rumba is played in 2/4 or 4/4 as is the case for the Guaguancó or the Yambú, the clave rhythm generally used is the following:

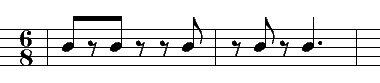

If the Rumba is played in 6/8 as in the Columbia, then this clave will be played:

Special thanks to Julien and his ultimate resource on cuban music and dance – this page is merely a translation.